Could We Code with Lunchables?

Ah, hrm — apologies. I, of course, mean Lunchables™️.

They are the future of programming. You’re hearing it here first.

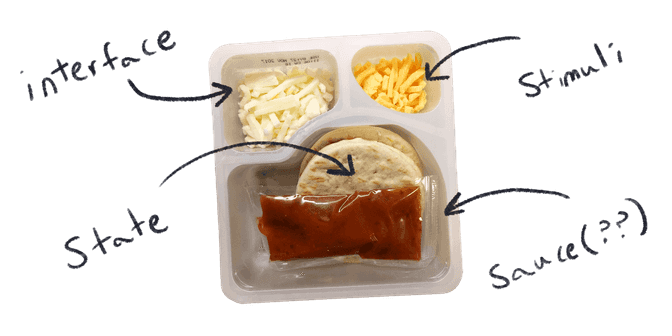

Behold!

But Actually

Creating software is hard. It’s par for the course to spend hours, days, or even longer attempting to do something you can describe in a sentence.

Is that just how it is?

Sometimes. Turing Award winner Fred Brooks differentiated between essential complexity and accidental complexity in his paper, “No Silver Bullet”. Essential complexity, the core difficulty of a task, is different than accidental complexity — or difficulties we create ourselves when using a solution. Brooks claimed most complexity (as of 1986) programmers deal with is essential.

There’s truth in that; we have come very far from coding on punched tape. And yet I believe there is still orders of magnitude more accidental complexity than necessary. Even with modern abstractions it can take months to create something as simple as a CRUD mobile app.

Could we just do:

search bar + results list + Twitter API = Twitter feed appOr if you want to make a game:

first person + punching + trees + cubes = MinecraftWhat about:

fur + purring + paws + friendship + withdrawn superiority =

Brandy, please come back I love youTo find out I’m going to propose we get a little hungry and talk some math. Just trust me on this one and perhaps grab a Lunchable!

An Associative Lunch is the Best Lunch

I have a confession.

At least 80% of the code I write is glue code — the code which simply integrates systems and third-party libraries together. Very little is original thought. I’m a fraud. But Mom, you said I am special!

And I wager I’m not alone on this. More work will be spent composing the work of others as we work at higher abstractions. This is good! But it does mean creep of accidental complexity in the quest to avoid essential complexity.

Let’s try to conquer this creep.

I’ve been getting deeper into the ML family of languages for a while and recently read through Bartosz Milewski’s “Category Theory for Programmers”. They both made me really appreciate some of the mathematical models behind how we code.

And right at the start is the semigroup — the definition of associative composition. It’s formally defined to be a set of elements, , and an operation, , where the following holds:

I had never heard of this before getting into functional programming. It’s a little strange that such a simple pattern isn’t part of the common programming vernacular!

Look Over There - a Semigroup!

Despite that, semigroups find themselves accidentally forming in code all the time. It’s a pattern that just makes sense.

The Salt and Pepper of Semigroups

From Life

As a human you expect basic semigroups like paint mixing, addition, and set union to work. An example of set union in everyday life is regretting things:

regret(regret(petBaboon, vegemite), badBlogPosts) ==

regret(petBaboon, regret(vegemite, badBlogPosts))It doesn’t matter in which order you regret things together — you’ll always regret everything in the end. Yay!

From Code

And as a coder, there are some types of data you expect to merge together consistently. Some examples are user permissions, configurations, and pure functions through composition. Here’s some configs getting merged:

default = {

favorites: [],

email: null,

}

zoo = {

favorites: [ 'giraffe', 'koala', 'tapir' ],

email: 'staff@zoo.org',

}

kris = {

favorites: [ 'aye-aye', 'lemur', 'tarsier' ],

email: 'kristoffer.wiggletown@zoo.org',

}

merged = {

favorites: [ 'aye-aye', 'lemur', 'tarsier', 'giraffe', 'koala', 'tapir' ],

email: 'kristoffer.wiggletown@zoo.org',

}

merged ==

merge( merge( default, zoo ), kris ) ==

merge( default, merge( zoo, kris ))The Professional’s Semigroups

Those are great, but let’s get fancier. Here are some higher-level constructs you’ll find around in modern code. I’ve been doing a lot of UI programming lately so that’ll be the theme.

UNIX pipelines

UNIX is famous for the philosophy of “do one thing and do it well”. The best example of this is the standard library of text processing commands!

# List of all sub-directories

ls -al | grep '^d'

# How many processes are running?

ps aux | wc -l

# Kill process by name

# Courtesy of https://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/30759/whats-a-good-example-of-piping-commands-together

ps aux | grep <name> | grep -v grep | awk '{print $2}' | xargs killWe could have aliased any amount of adjacent commands in the last example and it still would have worked. This follows as functions form a semigroup under composition. UNIX commands are really just effectful functions which take text as input and give it out as output.

Therefore, in theory, any UNIX command can compose with any other one. In practice, there are many commands which assume a certain text structure.

React

React has taken the web app programming by storm. Many quote the virtual DOM as it’s special sauce, but I disagree. It’s special flavor is declarative programming. It’s so simple I can describe the essence of the entire API as two functions:

That’s it. The power comes from virtual HTML and components being data themselves.

Every component is a pure function, which means we can use function composition without worry. And then to construct an entire UI we simply compose all components together underneath a root component!

Let’s check it out. Composition takes one of two forms in React’s templating language, JSX:

function nest( OuterComponent, innerElement ) {

return (

<OuterComponent>

{ innerElement }

</OuterComponent>

)

}

function wrap( ...components ) {

// Returns an array of components arguments

return components

}

// Let's construct a page

render(

nest( Page, wrap(

<Header />,

nest( Body, wrap(

<Title />,

<Content />,

<More />,

),

<Footer />,

)),

)You never see code like this; wrapping and nesting is just implicit in the JSX you write. However these two functions are the essential isolation of how you compose together components to create entire UIs.

And guess what? React components are a semigroup with either one of these functions. Ah, they strike again!

GraphQL

GraphQL is another Facebook technology which has taken the UI programming world by storm. It’s a query language designed to be the data parallel to React’s visual logic.

# Some basic client information

{

loggedIn {

name

email

}

}

# Specific page information

{

post(id: 45) {

title

author

content

}

}

# Made into one query

{

loggedIn {

name

email

}

post(id: 45) {

title

author

content

}

}Yeah that’s right — you literally just concatenate the top-level queries together.

That’s a semigroup!

For the skeptics out reading: yes, there are more complicated examples. Have no fear though, as top-level composition is always permitted. GraphQL is designed this way to permit reducing disjoint queries into a single, combined one for efficiency.

Semigroups All the Way Down

At this point you may be wondering what the hooplah is about. How does this let us create Twitter apps, block punching games, or recreating the best cat in the world?

It should get interesting if we explore the implications of designing systems with semigroups in mind. Only after a complete failure would we default to more complicated patterns.

To do so we’ll have to fix one thing. Looking back at the semigroup definition:

It’s only defined for elements in . This is a problem if we want to do something like:

search bar + results list + Twitter API = Twitter feed appWhat kind of set contains all three of those parts and knows an associative binary operator to combine them?

The answer I’ll offer is this:

- Consider the overall structure

- Break the structure down into parts

- If every part is a semigroup, then the overall structure is a semigroup too

In this case, perhaps apps have an overall structure where each part can be easily combined. To illustrate this, let’s consider the above pseudo-code with an explicit overall structure:

{ ui: search bar, data: none } +

{ ui: results list, data: none } +

{ ui: none, data: Twitter API } =

{

ui: search bar + results list,

data: Twitter API,

}In this way we can turn the problem of combining complicated, different things into the problem of combining simpler, similar things.

Creating Apps with Lunchables

Constructing advanced semigroups out of simpler ones reminds me of Lunchables! Each type of Lunchable has different isolated parts which work together to create a beautiful harmony of taste, wonder, and nostalgia in your mouth.

Okay, fine. Maybe they’re just crappy snacks marketed to tired parents.

But! Lunchables are similar to a well-architected app. You have your state, visuals, and stimuli. Stimuli affect the state which in turn is reflected in the visuals. Mmmmmmm what a recipe.

So we have a structure. Can we combine these together? In other words, can well-architected apps act as semigroups? I would have just said no if you asked me a few years ago. But, times are different. We might have the technology.

Let’s smash some apps together.

To do so, check out how we would smash each part together — the semigroups:

- Visuals: With React.js we usually just do what is explained above. A user-interface tree is composed of nesting and wrapping. GraphQL makes this even more true — each component’s data dependencies can be combined together into a single query. Therefore each component can live in it’s own isolated world waiting to be composed into a larger app.

- State: Redux serves us well in the React world. State can be split into smaller state trees and individual reducing logic. This logic is a semigroup with

combineReducers! - Stimuli: The best example of composition I know of here is child events in Purescript Pux.

If those make up an app, then we can start to compose entire apps together! Nifty. When I get a chance I really want to experiment making a proof-of-concept of this. Perhaps by recreating the Twitter app equation out of small, self-contained parts.

I do see one problem though, and that’s in glue code. Let’s go back to the Twitter app for a second:

search bar + results list + Twitter API = Twitter feed appThe semigroup needs to know how the results list relates to the Twitter API (its data source) and the search bar (an interim filtering step). The only problem is there’s no place for this information to go.

We could augment the binary operator to accept a third argument to configure the merging. It’s just that this would make the binary operator a ternary one, thus breaking the definition of semigroup altogether.

So our semigroup would no longer be a semigroup. Oh.

I haven’t really proved this, but I’m guessing you can just make the “configuration argument” a substructure in the app. This configuration part of your app defines how all the other parts link together. And if the configuration acts as a semigroup then you can still smash apps together in their entirety - configuration and all! Smashing.

This revised picture looks like this:

search bar + results list + Twitter API + configuration = Twitter feed appNice. I’ll update this post when I have a proof-of-concept working. For now, it’s just words.

Stranger Lunchables

Constructing apps like how we mix paint sounds really cool. Where else is it possible?

Just to take a peek in other areas of software:

- Distributed systems: Can you literally combine small backend systems together to implement a larger one? I know this has been explored thoroughly, but I can’t find any evidence that the goal was to make it literally as easy as a semigroup.

- Data processing: Backend pipelines are directed acyclic graphs, which have been known to compose together very well. Tensorflow and Luna Language explore this alongside many others.

- Robotics: I really have no idea about this one, but it would be cool to explore. An example would be creating a robot completely out of plug-n-play parts. Each part would bring any logic with it that the robot would need to merge its capabilities in.

Semigroups and additive composition surely aren’t new ideas. But I can’t shake the feeling it’s not even on the radar for most software platforms. Imperative stitching and ad-hoc configuration seems to be the norm, as if it’s accepted that’s just how software is created.

Let’s strive to be simpler. Even if it’s hard.