Hey Web, How Did We Get Here?

What a strange place.

Today’s websites can be email clients, 3D games, graphic design applications, word processors, crypto-currency miners, and more - the list just goes on.

What happened to just text?

I constantly use apps on the web. I read news on the web. I communicate with others on web. Hell, I make my living on the web. And yet I’m not even sure if I like it. It just, well, seems like a mistake sometimes.

As it turns out, I’m not alone. The most recent chatter on this has been “It’s time to kill the web” by Mike Hearn. There are dozens of us… dozens!

Although I agree with Mike’s points, I don’t want to kill the web. Well, at least just yet. Think of the cat GIFs!

Perhaps we can save it. And to do that, let’s reflect on where the web came from and what makes it special.

Get in the DeLorean

I didn’t know until recently that the World Wide Web is actually a version 2! It’s original design was meant to fix a single flaw of its predecessor, ENQUIRE.

ENQUIRE was the first attempt at a hypertext system by Sir Tim Berners-Lee at CERN. Being a good computer scientist, he wasn’t happy with any old information system. He wanted to record the connections between things in addition to traditional prose. “Things” being people, initiatives, software, hardware, and anything else someone with a “bad memory” at a world-class physics laboratory might want.

Beautiful. But it had one problem: ENQUIRE enforced two-way linking between pages. For example, if a person was linked to a program then the inverse automatically became true as well. That may sound great, but sometimes you don’t want to see all links coming to something. Too much information can be worse than none.

And to make it worse, two-way linking made it impossible to integrate with other systems. How do you two-way link to something if it doesn’t link back?

These issues made Sir Tim eventually revisit the problem. And thus, the World Wide Web was born with one way linking and the rest is history.

Well, the stuff before was history, too. Fine — I guess it’s all history, alright? Just keep reading!

Features, Features, Features

It was the summer of 1991

- There was video.

- There were no GIFs.

- There was no Javascript.

- There was no CSS.

Everything was text. There was only one browser and HTML. Well, less than 30 tags of HTML.

It became the fall of 2017

- 139 HTML tags.

- 5 widely used web browsers.

- CSS. An entirely new markup language with over 100 specifications. Oh and it happens to be Turing Complete.

- Javascript. A new scripting language created in 10 days. By some metrics it is the most popular language - by far.

And we haven’t even gotten started. Web browsers have evolved from being able to:

- View linked text documents with basic markup

to also being able to:

- Embed plugins like Flash, Java, and ActiveX

- View vector graphics

- Play audio

- Render 2D graphics

- Use custom fonts and typesetting

- Geolocate the device

- Online / offline detection

- Play video

- Offline web storage

- Download and parse files

- Cache websites for offline

- Low-level typed data

- Push notifications outside of browser

- Web sockets

…hold on there’s more…

- Threading through web workers

- Record audio, video, and pictures through the device

- Construct binary formats

- Detect if a page is visible

- Analyze and generate audio from scratch

- Render 3D graphics with a custom shader language

- Check battery status

- High resolution time

- Lock pointers for video games

- Trigger device vibrations

- Detect screen orientation

- Low-level cryptography

- Push data

- Speech-to-text and text-to-speech

- Generate audio through MIDI

- Permission

- Virtual reality

- Utilize a custom assembly language

Ummm, yeah. That’s a lot.

If that’s starting to sound like a full-blown computer, well that’s because it kinda is. Web browsers have evolved to be entire virtual machines.

In fact, they have now joined the ranks of the largest software projects of all time. For instance, here is one ranking by lines of code.

So… Why?

Good question, header text!

From what I can tell, the web’s success isn’t from a coherent plan. It’s more a product of novel design combined with historically great timing.

Reason #1 - The Power of the URI

URLs, and their more generic father the URI, are way more than just text strings at the top of your browser. They are:

- Unambiguous. A link should only ever point to one place.

- Readable. URLs don’t have to be readable but they usually are. Let’s not take this for granted! I’m looking at you, Google.

- Direct. Links can point to specific page locations, getting straight to the relevant content.

These qualities are essential to the goal of hypertext. URLs are a concept many other modern software ecosystems simply don’t have. This includes all popular operating systems. Imagine if any app on your computer or phone could direct you to any part of any other app!

It is such a powerful idea that other software systems have adopted it as well. For example, Hypercard is famous for apps being made out of unique, linkable, interactive pages. Sound interesting? Archive.org recently released emulated Hypercard apps for you to play with in your browser. Try it out!

Even desktop operating systems - the traditional platform - are tapping into URLs. An operating system has to manage all kinds of different resources and expose them to programs. Unix did so by making everything a file. Redox does so by making everything a URI.

Reason #2 - The Insta-factor

You want to read about Pokemon on Wikipedia? That Vimeo video? Prototype apps in Figma? Post dank memes on Tumblr? Read enraging comments on Reddit? Play Quake with your friends? Render the entire Earth in 3D?

Sure, go to this URL.

You want to use that program?

Okay, well… ummm… you’re on MacOS right? Maybe try the App Store, but their selection sucks. You should probably just search that on Google. Yeah that link looks legit, try that one. Okay sure, this looks good, where’s the download link? That’s it? Okay. Hrmm this is taking a moment, maybe I’ll see if Francis posted those Tahoe photos on Facebook. Huh, the lake was really clear that day wasn’t it. Did he actually bring — Ah it’s done! Alright, click the downloaded .dmg file. Click next a few times and hold on for a moment. It’s installing! Okay okay, it’s done.

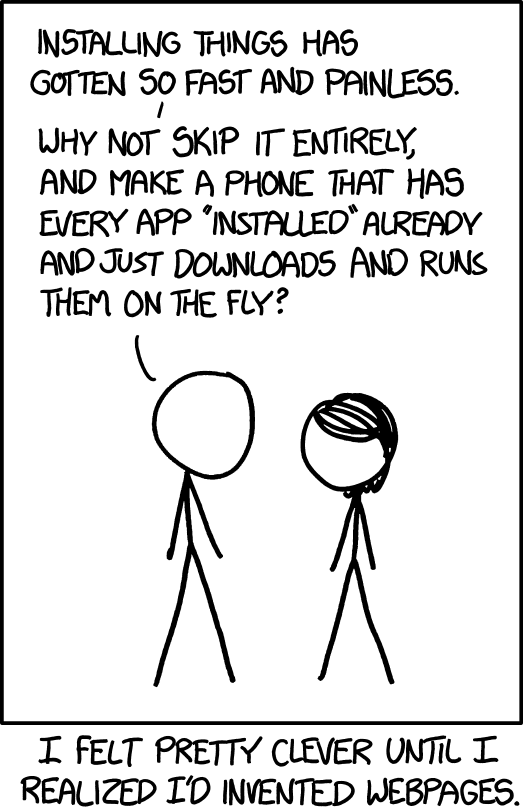

The impact of now cannot be overstated. The web’s humble origins from purely linked documents set our expectations:

Go to that URL, get that thing.

It’s just absolutely insane how much engineering work has gone into keeping that expectation even as content has rapidly advanced. Entire desktop-tier apps can now load in the browser in a few seconds with zero interaction from the user.

In a way, the web abstracts out the machine and brings us back to dumb computer terminals of the mainframe days. The concept of “installed” isn’t applicable anymore. Does it even matter if everything is instantly accessible at a URL?

Google has even gone full in on this idea with Chrome OS, blurring the lines between what’s the web and what’s on the machine. And it turns out to be doing very, very well.

Reason #3 - Everyone Loves the Sandbox

We would be in a lot of trouble if the web was simply instant apps at URLs.

It would be a chaotic mix of malware, instability, bloat, and utter chaos. Web browsers as containers are an absolute necessity.

But it goes further than that. Alongside the need for security is the need for standardization. The World Wide Web by definition is ubiquitous — it needs to work on every device for every user.

Sure, that’s not entirely true in practice. Censorship, compatibility issues, legacy browsers, and other issues prevent it from being absolute. But the important part has been the culture to fight those issues and keep it effectively ubiquitous.

Standardization also ensures developers have a consistent API. This is huge. Why develop content for wildly different devices when you could just put it on the web, making it a URL away? Cross-platform development just doesn’t make sense if the web will do the trick.

Reason #4 - Dat HTML

The web’s root as hypertext has given it an incredible quality. When everything’s a document you can treat everything like a document.

Okay, okay, that’s obvious. What I mean is that web sites can be easily consumed, parsed, played with, and extended in countless ways. HTML and the DOM — it’s Javascript reflection — have offered an unprecedent platform for flexibility.

In contrast, native apps are opaque black boxes. Their direct output of raster data to framebuffers contributes to their speed, but it also drastically limits how people can manipulate them.

Imagine being able to do the following with desktop programs or mobile apps:

- Universal ad blocking

- Change UIs of every app at will. Reorder sections, hide elements, and embed entirely new parts

- Save apps at arbitrary states as resolution-independent documents

- Built-in world-class debugging and introspection for all apps

- Robots for web scraping and automation

The web enables all of this. Can developers circumvent this? Sure - canvas rendering lets creators default back to opaque raster rendering. In practice this isn’t an issue - only the most bleeding-edge web apps need to escape the DOM to Pure Pixel-Land.

Reason #5 - The Demilitarized Zone of Tech

The last reason isn’t actually due to technology. It’s all about being in the right place at the right time.

Let’s go back to the early 2000’s and the dot-com bubble when it started to really gain steam. If you were developing a graphical application it was probably for Windows. At the time, Apple was just rising from the ashes with the recent release of the iMac.

And then there was the web: new and owned by no one.

It seemingly served as a neutral sandbox for tech giants to play in on equal footing. Companies could be rest assured Apple or Microsoft couldn’t assert control over their business. And this includes Apple and Microsoft.

New tech giants such as Google and Facebook could arise from nothing without worrying about the existing giants. I’m going to go out on a limb and say that’s why Google was so comfortable developing apps for the platform despite the incredibly retricting technical limitations.

Please Tread Carefully

Alright. So a 26-year old hypertext system for use at a physics lab has rapidly grown features, ending up as a viable alternative platform to native apps.

Do we continue forward? I, alongside others, strongly recommend against it. The web platform is a resounding success, but is also slowly growing for the sake of growing. There are consequences. The weight of complexity hinders browser implementations, annoys developers, and limits the potential of content.

The web won’t die, but it will certainly slow.

An initial reaction by some has been to burn it all down and try again. But we can’t. The web is simply too large and too important. It’s insane to suggest we should convince the majority of developers, companies, and users to set fire to the whole thing.

So let’s chart a new course but keep our ship. Let’s reflect on what makes the web great, leave our mistakes behind, and plot our course to the Promised Land.

What does the new course look like?

It looks like another blog post to write! 😀